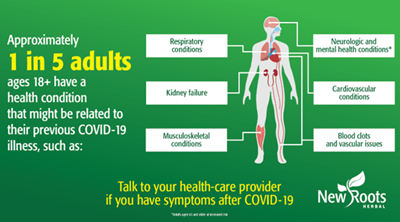

There is a tidal wave of post COVID conditions hitting us. According to Health Canada, if you are still experiencing physical or psychological symptoms more than 12 weeks after getting COVID 19, you suffer from a post–COVID 19 condition (also known as “long COVID”). 1 Based on one of the latest CDC reports, up to one in five adult COVID survivors suffers from a health condition that might be related to their previous COVID 19 illness.2

Although the research is still developing, the idea that an infectious agent may lead to long-term consequences has been potentially linked to other organisms, such as the Epstein-Barr virus that may lead to mononucleosis, a condition that can lead to long-term fatigue. Influenza virus has also been suspected of causing long-term fatigue in susceptible individuals. Some people can develop secondary infections such as ear or sinus infections, but by far the most common side effect associated with the flu is a postviral syndrome associated with symptoms of weakness and fatigue. The H1N1 influenza pandemic was shown to double the rate of chronic fatigue in one studied population. 3 This fatigue can last for weeks or months and is often associated with other symptoms such as trouble concentrating and headaches. The trigger for this postviral fatigue appears to be the virus itself. 4 The reason for the fatigue is uncertain but it is thought to occur from inflammation in the brain signalling the body to suppress physical activity to recover. 5 Observations from previous coronavirus infections including MERS and SARS showed that survivors could experience symptoms for up to four years. 6,7

Within the current pandemic, research demonstrates that infection with COVID‑19 can lead to long-term relapsing fatigue and shortness of breath. It is estimated that up one third of patients have persisting symptoms for six months after contracting the infection. 8 Researchers have suggested that the long-term symptoms associated with COVID‑19 are often like myalgic encephalomyelitis, also known as chronic fatigue syndrome. 9 But symptoms are not limited to fatigue, as we will see further down. Shortness of breath, cognitive impairment, memory loss, anxiety, depression, insomnia, muscle pain, joint pain, headaches, kidney outcomes, cough, air loss, wheezing, cardiac issues, increased heartbeat, chest pain, altered smell, altered taste, and diarrhea were other common long-term symptoms associated with post‑COVID. 10,11,12,13

When it comes to the neurological symptoms resulting from post–COVID‑19, they appear to closely match the symptoms seen with chronic fatigue syndrome and include:14

- Profound fatigue of defined onset, not caused by excessive exertion or relieved by rest, with substantial reduction in the ability to engage in occupational, educational, personal, and social activities for more than six months;

- Postexertional malaise;

- Unrefreshing sleep; and

- Cognitive impairment or difficulty standing due to fatigue.

Any COVID‑19 survivor can develop long‑COVID syndrome, and it appears that neither the age of the patient nor the severity of the initial infection predicts who ends up with long-term problems, although there are trends. It appears that people who had mild illness are more predisposed to develop long COVID compared to those who were hospitalized.15

So, who gets into trouble following COVID‑19 and what are their symptoms?

In a treatment group comprised of 225 patients in the UK suffering from post‑COVID conditions, the following demographics were noted: the average age of participants was 48 years, 68% of patients were female, 74% had been admitted to the hospital, 82% were infected in the initial phase of the pandemic, and 54% were unable to work or had to reduce their work hours. 16 Of the patients treated, 70% needed help with fatigue management, 51% for breathlessness, and 12% for cognitive problems. Also, in a study involving 181,280 participants, it was shown that people who had had COVID‑19 were about 40% more likely to develop diabetes up to a year later than were participants in the control groups. 17

General Research by Symptom Cluster Fatigue

Post–COVID‑19 fatigue is prevalent and commonly reported in the post–COVID‑19 period.18

The latest meta-analysis showed that 32% of patients still experienced fatigue 12 weeks or more following COVID‑19 diagnosis.19

Respiratory Symptoms

At three months postinfection, between 25% and 71% of patients had impaired lung-function tests or lung-imaging studies.20

In hospitalized patients, 42% of patients had abnormal lung function or imaging studies three months postinfection.21

Studies show lung fibrosis or scarring lasting up to six months after hospital discharge. 22,23

In young patients, 45 days post–COVID‑19 infection, 19% of participants had a decrease of more than 10% in V̇O₂ max.

Neurological Issues

Symptoms include depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, memory loss, and fatigue. 25

The exact cause of these symptoms is not clearly understood, but inflammation of the nervous system may be a possible underlying mechanism.26

In a small study looking at brain imaging in 60 patients three months post–COVID‑19 infection, 55% of patients had neurological symptoms.27

COVID‑19 results in delirium in about 20–30% of hospitalized patients. Long-term neurological symptoms are more likely in those patients.28

In 236,379 COVID‑19 survivors, about a third received a neuropsychiatric diagnosis such as stroke, dementia, insomnia, anxiety, or mood disorders within six months post–COVID‑19. These disorders were 44% more common than in influenza survivors. 29

Cardiovascular Problems

Cardiac injury is also possible with COVID‑19: “beyond the first 30 days after infection, individuals with COVID‑19 are at increased risk of incident cardiovascular disease spanning several categories, including cerebrovascular disorders, dysrhythmias, ischemic and non-ischemic heart disease, pericarditis, myocarditis, heart failure and thromboembolic disease.” 30

In a study of 26 college athletes with asymptomatic COVID‑19, 46% of them ended up with inflammation of the cardiac muscle.31

Cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, heart palpitations, and tachycardia commonly persist among COVID‑19 survivors for up to six months.32,33

Other Problems

Inflammation caused by COVID‑19 can wreak havoc on other organs. In one study, at four-month follow-up, at least one radiological abnormality of the lungs, heart, liver, pancreas, kidneys, or spleen was present in 66% of survivors. 34

In a retrospective cohort study, among 193,113 COVID-19 patients aged ≤65 years, new onset-diabetes was the sixth most common post-acute clinical sequelae over a median follow-up of 2.9 months.35

Treatment Options

Unfortunately, only preliminary information is available when it comes to improving symptoms associated with post‑COVID. Some studies show that rehabilitation through breathing exercises and mild cardiovascular exercise can be helpful when it comes to fatigue and shortness of breath.36,37

Rehabilitation can be more challenging for survivors of severe COVID‑19, especially if pulmonary or cardiac damage has occurred. Rehabilitation must be done carefully. One study showed that 85.9% of participants with post–COVID‑19 experienced a worsening of symptoms following mental or physical activities. 38

Models established in the UK show that a multifaceted approach, with multiple intervention pathways based on severity of presenting symptoms, is needed when it comes to caring for post–COVID‑19 patients. 39 Key measures included assessment for fatigue, breathlessness, deconditioning, poor cognition, anxiety, depression, and pain. Criteria for escalation to care provided by a specialist included nonresolving breathlessness, unexplained chest pain or palpitations, uncontrolled pain, deterioration or lack of improvements in symptoms, and hospitalization for mental health reasons.40

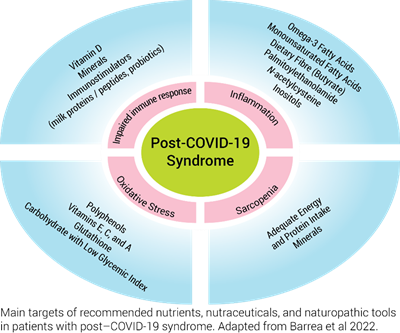

Nutritional Considerations

In terms of nutrition and supplementation, there is limited information available. However, one research team looked at the available information and proposed nutritional support based on theoretical benefits to relieve fatigue. 42

It is also suggested that a diet high in protein, fruits, and vegetables such as the Mediterranean diet may be beneficial.43

Supplementation Guidelines

In a nonblinded study, the supplementation group received a multivitamin food supplement containing B‑group vitamins, vitamin C, vitamin D, acetyl-ʟ‑carnitine, and hydroxytyrosol. Preliminary results show that the supplement might be able to help patients recover from fatigue and tiredness. 44

Preliminary research showed that COVID‑19 patients were more likely to suffer from selenium or vitamin D deficiency. 45 One review looking at the treatment of post–COVID‑19 with intravenous vitamin C showed that of nine studies, seven resulted in significant decreases in levels of fatigue. 46 The authors concluded that “the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, endothelial-restoring, and immunomodulatory effects of high-dose IV vitamin C might be a suitable treatment option (for post‑viral fatigue, especially long‑COVID).” 47,48

Other potentially beneficial interventions include the support of the gut microflora through supplementation with probiotics, 49,50 a support at the cellular level with coenzyme Q₁₀ to fight oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, and ultimately lessening chronic fatigue symptoms from SARS‑CoV‑19. 51

Supplementation with 1.5–3 g of omega‑3 fatty acids per day, a natural anti‑inflammatory, as well as antioxidant nutraceuticals in general may also help to cope with oxidative stress induced by COVID‑19.52

Conclusion

International studies show that, for 91% of patients, time to recovery exceeded 35 weeks, suggesting that implementing a rehabilitation and recovery program may be important to consider. 53 Seeking help is the first step to better understand what is safe and effective for your personal health status.

by Ludovic Brunel, ND

References: 1. Government of Canada. Post COVID‑19 condition (long COVID). https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/symptoms/post-COVID‑19-condition.html · Modified 2022‑05‑30. · Accessed 2022‑05‑31. 2. Bull‑Otterson, L., S. Baca, S. Saydah, T.K. Boehmer, S. Adjei, S. Gray, and A.M. Harris. “Post–COVID Conditions Among Adult COVID‑19 Survivors Aged 18–64 and ≥65 Years – United States, March 2020 – November 2021.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 71, No. 21 (2022): 713–717. 3. Magnus, P., N. Gunnes, K. Tveito, I.J. Bakken, S. Ghaderi, C. Stoltenberg, M. Hornig, W.I. Lipkin, L. Trogstad, and S.E. Håberg. “Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) is associated with pandemic influenza infection, but not with an adjuvanted pandemic influenza vaccine.” Vaccine, Vol. 33, No. 46 (2015): 6173–6177. 4. Poole‑Wright, K., F. Gaughran, R. Evans, and T. Chalder. “Fatigue outcomes following coronavirus or influenza virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” medRxiv, 2020‑12 (preprint, not peer‑reviewed). 5. Yamato, M., and Y. Kataoka. “Fatigue sensation following peripheral viral infection is triggered by neuroinflammation: Who will answer these questions?” Neural Regeneration Research, Vol. 10, No. 2 (2015): 203–204. 6. Lee, S.H., H.‑S. Shin, H.Y. Park, J.L. Kim, J.J. Lee, H. Lee, S.‑D. Won, and W. Han. “Depression as a mediator of chronic fatigue and post-traumatic stress symptoms in Middle East respiratory syndrome survivors.” Psychiatry Investigation, Vol. 16, No. 1 (2019): 59–64. 7. Lam, M.H.‑B., Y.‑K. Wing, M.W.‑M. Yu, C.‑M. Leung, R.C.W. Ma, A.P.S. Kong, W.Y. So, S.Y.‑Y. Fong, and S.‑P. Lam. “Mental morbidities and chronic fatigue in severe acute respiratory syndrome survivors: Long-term follow-up.” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 169, No. 22 (2009): 2142–2147. 8. Logue, J.K., N.M. Franko, D.J. McCulloch, D. McDonald, A. Magedson, C.R. Wolf, and H.Y. Chu. “Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID‑19 infection.” JAMA Network Open, Vol. 4, No. 2 (2021): e210830. 9. Poenaru, S., S.J. Abdallah, V. Corrales‑Medina, and J. Cowan. “COVID‑19 and post‑infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A narrative review.” Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease, Vol. 8 (2021): 20499361211009385. 10. Arnold, D.T., F.W. Hamilton, A. Milne, A.J. Morley, J. Viner, M. Attwood, A. Noel, et al. “Patient outcomes after hospitalization with COVID‑19 and implications for follow‑up: Results from a prospective UK cohort.” Thorax, Vol. 76, No. 4 (2020): 399–401. 11. Cirulli, E.T., K.M. Schiabor Barrett, S. Riffle, A. Bolze, I. Neveux, S. Dabe, J.J. Grzymski, J.T. Lu, and N.L. Washington. “Long-term COVID‑19 symptoms in a large unselected population.” medRxiv, 2020‑12 (preprint, not peer‑reviewed). 12. Davis, H.E., G.S. Assaf, L. McCorkell, H. Wei, R.J. Low, Y. Re’em, S. Redfield, J.P. Austin, and A. Akrami. “Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact.” medRxiv, 2021‑04 (preprint, not peer‑reviewed). 13. Bowe, B., Y. Xie, E. Xu, and Z. Al‑Aly. “Kidney outcomes in long COVID.” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, Vol. 32, No. 11 (2021): 2851–2862. 14. González‑Hermosillo, J.A., J.P. Martínez‑López, S.A. Carrillo‑Lampón, D. Ruiz‑Ojeda, S. Herrera‑Ramírez, L.M. Amezcua‑Guerra, and M.D.R. Martínez‑Alvarado. “Post‑acute COVID‑19 symptoms, a potential link with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A 6-month survey in a Mexican cohort.” Brain Sciences, Vol. 11, No. 6 (2021): 760. 15. [No authors listed.] “Patients diagnosed with post‑COVID conditions—An analysis of private healthcare claims using the official ICD-10 diagnostic code.” FAIR Health White Paper, 2022. 16. Parkin, A., J. Davison, R. Tarrant, D. Ross, S. Halpin, A. Simms, R. Salman, and M. Sivan. “A multidisciplinary NHS COVID‑19 service to manage post‑COVID‑19 syndrome in the community.” Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, Vol. 12 (2021): 21501327211010994. 17. Xie, Y., and Z. Al‑Aly. “Risks and burdens of incident diabetes in long COVID: A cohort study.” The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology, Vol. 10, No. 5 (2022): 311–321. 18. Barrea, L., W.B. Grant, E. Frias‑Toral, C. Vetrani, L. Verde, G. de Alteriis, A. Docimo, S. Savastano, A. Colao, and G. Muscogiuri. “Dietary recommendations for post‑COVID‑19 syndrome.” Nutrients, Vol. 14, No. 6 (2022): 1305. 19. Ceban, F., S. Ling, L.M.W. Lui, Y. Lee, H. Gill, K.M. Teopiz, N.B. Rodrigues, et al. “Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post‑COVID‑19 syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, Vol. 101 (2022): 93–135. 20. Zhao, Y.‑M., Y.‑M. Shang, W.‑B. Song, Q.‑Q. Li, H. Xie, Q.‑F. Xu, J.‑L. Jia, et al. “Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID‑19 survivors three months after recovery.” EClinicalMedicine, Vol. 25 (2020): 100463. 21. Huang, C., L. Huang, Y. Wang, X. Li, L. Ren, X. Gu, L. Kang, et al. “6‑month consequences of COVID‑19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study.” The Lancet, Vol. 397, No. 10270 (2021): 220–232. 22. Bellan, M., D. Soddu, P.E. Balbo, A. Baricich, P. Zeppegno, G.C. Avanzi, G. Baldon, et al. “Respiratory and psychophysical sequelae among patients with COVID‑19 four months after hospital discharge.” JAMA Network Open, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2021): e2036142. 23. Liu, D., W. Zhang, F. Pan, L. Li, L. Yang, D. Zheng, J. Wang, and B. Liang. “The pulmonary sequalae in discharged patients with COVID‑19: A short-term observational study.” Respiratory Research, Vol. 21, No. 1 (2020): 125. 24. Crameri, G.A.G., M. Bielecki, R. Züst, T.W. Buehrer, Z. Stanga, and J.W. Deuel. « Reduced maximal aerobic capacity after COVID‑19 in young adult recruits, Switzerland, May 2020.” Euro Surveillance, Vol. 25, No. 36 (2020): 2001542. 25. Rogers, J.P., E. Chesney, D. Oliver, T.A. Pollak, P. McGuire, P. Fusar‑Poli, M.S. Zandi, G. Lewis, and A.S. David. “Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe corona virus infections: A systematic review and meta‑analysis with comparison to the COVID‑19 pandemic.” The Lancet. Psychiatry, Vol. 7, No. 7 (2020): 611–627. 26. Matschke, J., M. Lütgehetmann, C. Hagel, J.P. Sperhake, A.S. Schröder, C. Edler, H. Mushumba, et al. “Neuropathology of patients with COVID‑19 in Germany: A post‑mortem case series.” The Lancet. Neurology, Vol. 19, No. 11 (2020): 919–929. 27. Lu, Y., X. Li, D. Geng, N. Mei, P.‑Y. Wu, C.‑C. Huang, T. Jia, et al. « Cerebral micro‑structural changes in COVID‑19 patients – An MRI‑based 3‑month follow‑up study.” EClinicalMedicine, Vol. 25 (2020): 100484. Mao, L., H. Jin, M. Wang, Y. Hu, S. Chen, Q. He, J. Chang, et al. “Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China.” JAMA Neurology, Vol. 77, No. 6 (2020): 683–690. 29. Taquet, M., J.R. Geddes, M. Husain, S. Luciano, and P.J. Harrison. “6‑month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID‑19: A retrospective cohort study using electronic health records.” The Lancet. Psychiatry, Vol. 8, No. 5 (2021): 416–427. 30. Xie, Y., E. Xu, B. Bowe, and Z. Al‑Aly. “Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID‑19.” Nature Medicine, Vol. 28, No. 3 (2022): 583–590. 31. Rajpal, S., M.S. Tong, J. Borchers, K.M. Zareba, T.P. Obarski, O.P. Simonetti, and C.J. Daniels. “Cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in competitive athletes recovering from COVID‑19 infection.” JAMA Cardiology, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2021): 116–118. 32. Dennis, A., M. Wamil, J. Alberts, J. Oben, D.J. Cuthbertson, D. Wootton, M. Crooks, et al. “Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post‑COVID‑19 syndrome: A prospective, community-based study.” BMJ Open, Vol. 11, No. 3 (2021): e048391. 33. Carfi, A., R. Bernabei, F. Landi; Gemelli Against COVID‑19 Post‑Acute Care Study Group. “Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID‑19.” JAMA, Vol. 324, No. 6 (2020): 603–605. 34. Dennis A, Wamil M, Alberts J, et al. . Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post-COVID‑19 syndrome: A prospective, community-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e048391. 35. Daugherty, S.E., Y. Guo, K. Heath, M.C. Dasmariñas, K.G. Jubilo, J. Samranvedhya, M. Lipsitch, and K. Cohen. “SARS‑CoV‑2 infection and risk of clinical sequelae during the post‑acute phase: A retrospective cohort study.” medRxiv, 2021‑03 (preprint, not peer‑reviewed). 36. Greenhalgh, T., M. Knight, C. A’Court, M. Buxton, and L. Husain. “Management of post‑acute COVID‑19 in primary care.” BMJ, Vol. 370 (2020): m3026. 37. Wang, T.J., B. Chau, M. Lui, G.‑T. Lam, N. Lin, and S. Humbert. “Physical medicine and rehabilitation and pulmonary rehabilitation for COVID‑19.” American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Vol. 99, No. 9 (2020): 769–774. 38. Davis et al. “Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort.” op. cit. 39. Parkin et al. “A multidisciplinary NHS COVID‑19 service.” op. cit. 40. Parkin et al. “A multidisciplinary NHS COVID‑19 service.” op. cit. 41. Cawood, A.L., E.R. Walters, T.R. Smith, R.H. Sipaul, and R.J. Stratton. “A review of nutrition support guidelines for individuals with or recovering from COVID‑19 in the community.” Nutrients, Vol. 12 (2020): 3230. 42. Naureen, Z., A. Dautaj, S. Nodari, F. Fioretti, K. Dhuli, K. Anpilogov, L. Lorusso, et al. “Proposal of a food supplement for the management of post‑COVID syndrome.” European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, Vol. 25, No. 1 Suppl. (2021): 67–73. 43. Barrea et al. “Dietary recommendations for post‑COVID‑19 syndrome.” op. cit. 44. Naureen et al. “Proposal of a food supplement.” op. cit. 45. Cawood et al. “A review of nutrition support guidelines.” op. cit. 46. Vollbracht, C., and K. Kraft. “Feasibility of vitamin C in the treatment of post viral fatigue with focus on long COVID, based on a systematic review of IV vitamin C on fatigue.” Nutrients, Vol. 13, No. 4 (2021): 1154. 47. Vollbracht and Kraft. “Feasibility of vitamin C in the treatment of post viral fatigue.” op. cit. 48. Vollbracht, C., and K. Kraft. “Oxidative stress and hyper-inflammation as major drivers of severe COVID‑19 and long COVID: Implications for the benefit of high-dose intravenous vitamin C.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, Vol. 13 (2022): 899198. 49. Alharbi, K.S., Y.Singh, W.H. Almalki, S. Rawat, O. Afzal, A.S. Alfawaz Altamimi, I. Kazmi, et al. “Gut microbiota disruption in COVID‑19 or post‑COVID illness association with severity biomarkers: A possible role of pre / pro-biotics in manipulating microflora.” Chemico-Biological Interactons, Vol. 358 (2022): 109898. 50. Santinelli, L., L. Laghi, G.P. Innocenti, C. Pinacchio, P. Vassalini, L. Celani, A. Lazzaro, et al. “Oral bacteriotherapy reduces the occurrence of chronic fatigue in COVID‑19 patients.” Frontiers in Nutrition, Vol. 8 (2022): 756177. 51. Wood, E., K.H. Hall, and W. Tate. “Role of mitochondria, oxidative stress and the response to antioxidants in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A possible approach to SARS‑CoV‑2 ‘long-haulers’?” Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine, Vol. 7, No. 1 (2021): 14–26. 52. Barrea et al. “Dietary recommendations for post‑COVID‑19 syndrome.” op. cit. 53. Davis et al. “Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort.” op. cit.